Dynamics 365 F&O Integration Case Study: Part III

#The Destination

#Introduction

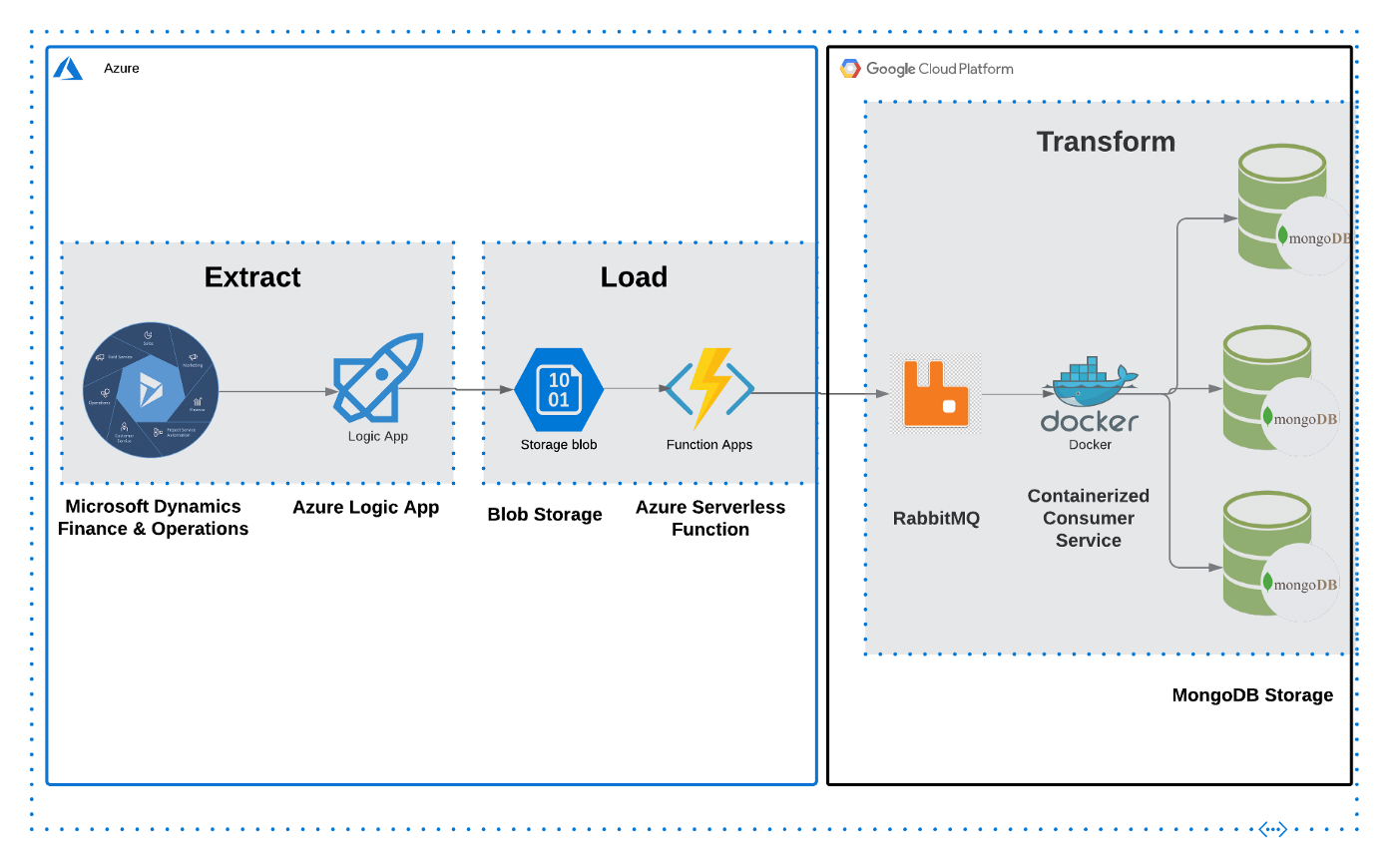

In the past articles in this case study, we went over the source systems and the middleware that comprise the data pipeline. Now we’ll discuss the destination components and how they communicate with the other parts to make up the end-to-end pipeline and complete the event-driven design. These components are the message broker, the consumer service, and the destination database (MongoDB).

Message Queues & Brokers⌗

Message queues have been defined as “a form of asynchronous service-to-service communication used in serverless and microservices architecture”. In less buzz wordy terms, it’s a software component that acts as a hub for messages from a source (also known as a producer) to a destination (also known as a consumer). Instead of one system sending data directly to another, this acts as a middle man of sorts. This “decoupling” of software components is a core part of the modern system design for cloud based software and applications. Something to note is the concept of asynchronous communication, which is really any sort of communication that includes sending someone a message and not expecting an immediate response.

While there are different variations of queues and how they handle messages (first in, first out as an example), for this particular guide we’ll talk about RabbitMQ. RabbitMQ, or just Rabbit, is an open-source message broker. A message broker is a variation of the concept of a message queue, still acting as a middle-man in the transfer of messages, but including capabilities like parallel processing from multiple consumers, transformation of the data/messages. It can help translate between different messaging protocols, as opposed to just sending it back and forth with no manipulation.

Due to its open-source nature, you can use RabbitMQ locally and on the cloud without having to pay for anything other than compute resources to host on the cloud. Rabbit can be deployed using Docker, Kubernetes, or just by downloading it on your machine, (https://www.rabbitmq.com/download.html). A popular alternative is Apache Kafka, which has its own pros and cons, and can also be deployed using Docker or by installing it locally. Kafka is usually compared to a queuing system such as RabbitMQ. What makes the difference is that after consuming the log, Kafka doesn’t delete it. In that way, messages stay in Kafka longer, and they can be replayed. Rabbit uses a pub/sub pattern, with consumers “subscribing” to a particular topic and Rabbit “pushing” the information to the consumers.

Consumer & Destination Database⌗

The queue needs somewhere to send the message that it receives. This is where the consumer comes in. A consumer is any piece of software that communicates with the queue or the broker, and does something with the data that it receives. Typically a micro-service, this software can be written in your preferred language, although in our case we wrote it in Go.

Our solution concluded with a microservice written in Go that acted as a consumer, cleaned the data up, and upserted into a MongoDB cluster. I’ve included some snippets from the consumer we developed to help demonstrate the basic parts of this part of the system (connect to the queue, get the message data, and finally send it to the database). It should be noted that our production code was different due to the unique data manipulation that the client needed and the amount of messages we needed to handle.

It’s also worthwhile to mention my assumption as a writer that the reader knows the basics of Go so I won’t spend time talking too much about the intricacies of the language and the development environment (that is a different post entirely).

package main

import (

"encoding/json"

"fmt"

"io"

"log"

"net"

"time"

"github.com/streadway/amqp"

)

func main() {

fmt.Println("Connecting to RabbitMQ")

url := "RABBIT-URL-GOES-HERE"

connection, err := amqp.Dial(url)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println("Error connecting with dial: ", err)

}

defer connection.Close()

channel, err := connection.Channel()

if err != nil {

fmt.Println("Could not create channel from rabbit connection: ", err)

}

defer channel.Close()

queueName := "QUEUE-NAME-GOES-HERE"

// The variable m is used here to declare the type of rabbitmq we are using. This is a solution to the error, "inequivalent arg 'x-queue-type' for queue 'queuename' in vhost '/': received none but current is the value 'classic' of type 'longstr"

m := make(amqp.Table)

m["x-queue-type"] = "classic"

q, err := channel.QueueDeclare(

queueName, //name

true, //durable

false, //deleted when unused

false, // exclusive

false, //no-wait

m, //arguments

)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println("Error declaring queue: ", err)

}

msgs, err := channel.Consume(

q.Name, //queue

"", //consumer

true, //auto-ack

false, //exclusive

false, //no-local

false, //no-wait

nil, //args

)

}

In this initial part of the code, we’re using the amqp package to connect to the queue and consume the messages in it. Once consumed, the information is stored in the msgs variable (type <-chan amqp.Delivery) that is returned by the Consume method.

package main

import (

"context"

"encoding/json"

"fmt"

"strconv"

"time"

"go.mongodb.org/mongo-driver/bson"

"go.mongodb.org/mongo-driver/bson/primitive"

"go.mongodb.org/mongo-driver/mongo"

"go.mongodb.org/mongo-driver/mongo/options"

)

type Message struct {

Name string `json:"Name" bson:"Name"`

Value string `json:"Value" bson:"Value"`

}

var db *mongo.Client

var CRUDdb *mongo.Collection

var mongoCTX context.Context

func main() {

msgs, err := channel.Consume(

q.Name, //queue

"", //consumer

true, //auto-ack

false, //exclusive

false, //no-local

false, //no-wait

nil, //args

)

/////code block from above

//connecting to MongoDB

fmt.Println("connecting to MongoDB......")

mongoCTX = context.Background()

db, err = mongo.Connect(mongoCTX, options.Client().ApplyURI("DB-URI-GOESS-HERE"))

if err != nil {

fmt.Println("Failed with applying URI", err)

log.Fatal(err)

}

err = db.Ping(mongoCTX, nil)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println("Failed to connect to db", err)

log.Fatal(err)

} else {

fmt.Println("Connected to mongo")

}

CRUDdb = db.Database("DB-NAME-GOES-HERE").Collection("COLLECTION-NAME-GOES-HERE")

// starting a go func to handle the range of messages efficiently

go func() {

for d := range msgs {

msgCount++

var messagestruct Message

fmt.Printf("\nMessage Count: %d, Message Body: %s\n", msgCount, d.Body)

//here we're essentially "mapping" (unmarshaling) the content of the message to the struct we declared above

err := json.Unmarshal(d.Body, &messagestruct)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println("Error unmarshaling message body to message struct", err)

}

result, err := CRUDdb.InsertOne(ctx, messagestruct)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println("Error Inserting Document ----> ", err)

}

fmt.Println("Here is the create result ", result)

}

}()

}

In this second block of code, we’re connecting to the Mongo database instance and giving it a ping just to make sure we connected successfully. Then, we enter into a go routine to handle the messages using threads in case there’s a large amount of data in the queue (see multi-threading if you need more info around the concept). In this go routine, we unmarshal the body of the message into our struct so that it can be represented in both JSON and BSON (need this data representation in order to insert into the database).

For context, MongoDB is a document based database (see NoSQL) that manages data not in tables or rows, but in essentially JSON-based format (i.e. BSON). Data is represented as key/value pairs, and is inherently more flexible than traditional SQL databases due to its lack of an enforced schema. It is important to note that in production, we utilized the upsert capability of MongoDB, which inserts data only if the database doesn’t find that the document already exists in the records. We used upsert because our production system is moving changed data, so we want to make sure that we only update the documents that have changed.

Conclusion⌗

Working on this particular project was exciting due to the many different services and software we implemented. From working on serverless functions to document based databases, this pipeline had a bit of everything (and it also optimized for cost & performance, which is the goal at the end of the day). I’ve included a visual of the entire system from beginning to end and its components, which I also included in the original post of this series, way back when. If you read this whole thing, I appreciate it and I hope you got something useful out of it. If neither of those things are true, then that’s okay too.