DrawDrills (the backend)

What is DrawDrills

DrawDrills is a free tool for artists to create and share convenient practice regimens online. It’s like rote-learning, but for drawing. The original inspiration for the tool came from artists close to the team at Arcvale and was then further developed by our studio as a tool to help our internal team of artists. As we began sharing DrawDrills with some friends and other artists, we realized it was something that people outside of Arcvale might like to use, and started development for the public. DrawDrills is currently available at https://www.drawdrills.org (we are at our beta release and thus reserve the right to make mistakes).

We spent the better part of a year getting the internal tool ready for public release and now that it is in beta, we wanted to start sharing what we learned through the process of building it out. This particular post will cover the backend of the application, specifically the APIs we developed for it. The DrawDrills team has evolved over time, but it has consistently consisted of a couple front end developers, a designer, and myself acting as both a product manager and backend developer. For this application, we developed the backend in Golang and GraphQL and used a MongoDB database. The rest of this post will cover a high level primer on Go, GraphQL, and some examples of the kind of functionality we were able to create with this stack.

What is Golang

So, now that we covered the initial context, let’s start here: “What is golang?” (hereafter referred to as Go). Well, Go is a programming language that I happen to be a fan of. Open source but supported by Google, Go was released to the public in 2012, after being announced in 2009. The birth of Go stems from a small group of developers growing tired of the existing languages that they were developing in and their various issues (mostly C++ and its compile times). After meeting at Google and working on large, complex systems that needed high performance networking and multiprocessing, this initial core group of developers realized they wanted a language that essentially had all the best design aspects of their existing stack and addressed all the issues, something along these lines:

- It should have the runtime performance and static typing of something like C

- It should also have the readability and usability of Python or JS

I’m a tad biased since Go is the first language I picked up after Python, but I like to think that they hit the spirit of these aspects. But it doesn’t matter what I think, it’s what the developer community thinks that truly matters. On that note, let’s take a look at Go’s popularity amongst developers:

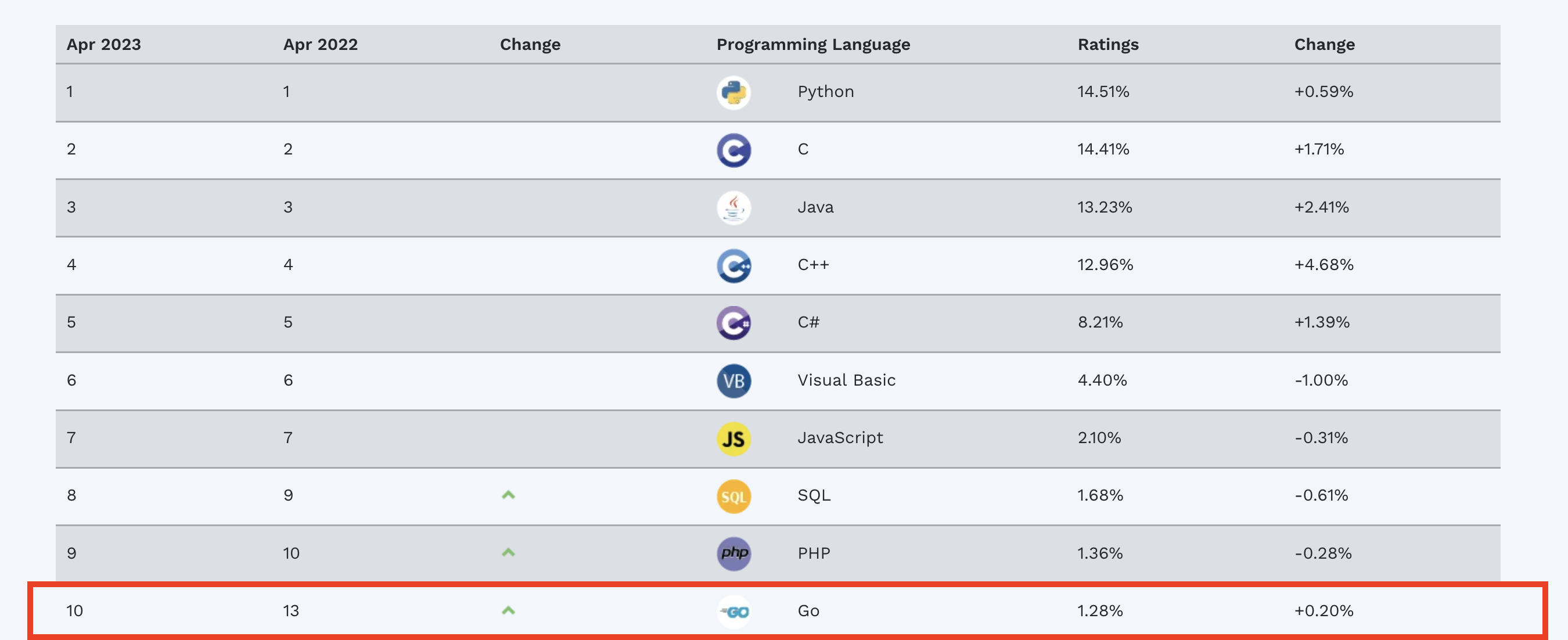

In TIOBE’s Programming Community April 2023 index, Go cracked the top ten most popular programming languages (moving up a couple places from their previous position in the top 15):

Source: www.tiobe.com

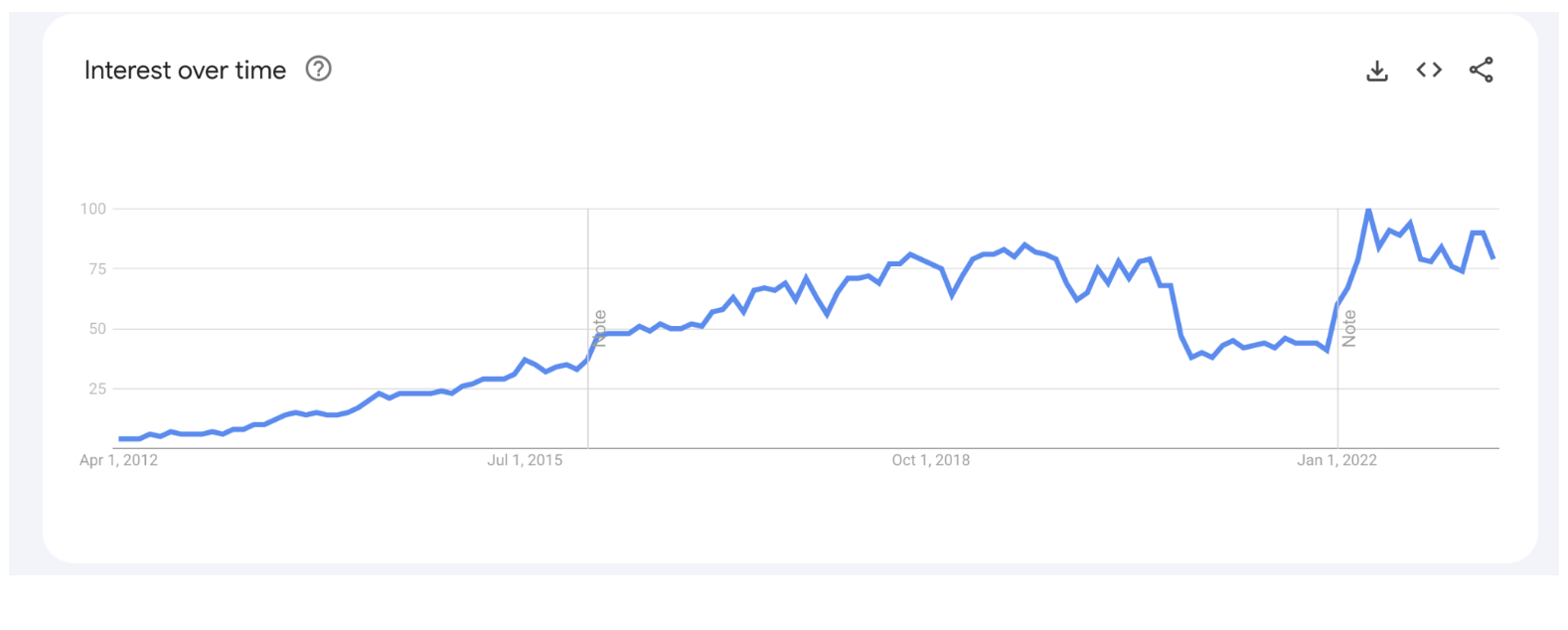

Looking at the Google search trend for “golang”, we can see a rather large increase of interest since 2012 as well:

Your immediate thought at this point might be something along the lines of, “Ok I get that some guys out of Google made it and it combines aspects of other languages and it sure seems popular, but why does everyone else actually like it?” Glad you asked, dear reader. I’ll lay out some of the objective and subjective takes that are used to justify the adoption of Go:

- Concurrency: Go was developed with concurrency and multi-core processors in mind and as such, supports multithreading, asynchrony, and multiprocessing natively.

- Garbage Collector: while not the first one to use a garbage collector, Go brings all the benefits that all languages with garbage collectors provide, with its own twist: it runs its garbage collection on a dedicated core to lower any potential impact to latency

- Simple Syntax: take it from someone who is much closer to an enthusiast than a West Coast capital E Software Engineer, Go’s syntax is quite small compared to other languages and is heavily opinionated when it comes to code readability and formatting. This makes it very easy to ramp up when a junior developer is learning it or when you need to quickly onboard team members to your project.

- Modern Design Considerations: I touched on some of the design considerations that the original language developers used to guide them, but it’s worth highlighting in this section as well. Go was designed with the modern development ecosystem in mind, and as such is incredibly well suited to run in the cloud-centric world we operate in these days. Go can be compiled on any machine, is built for performance (it do be fast), and supports easy package importing.

As we can see, Go is quite good at a lot of things that other languages are not so strong at. It definitely is not perfect (the cons of working with Go deserve a whole other piece), but due to its relative syntax simplicity, high performance with our use case (microservices, APIs, etc), and general tooling, we decided to build our backend with it.

What is GraphQL

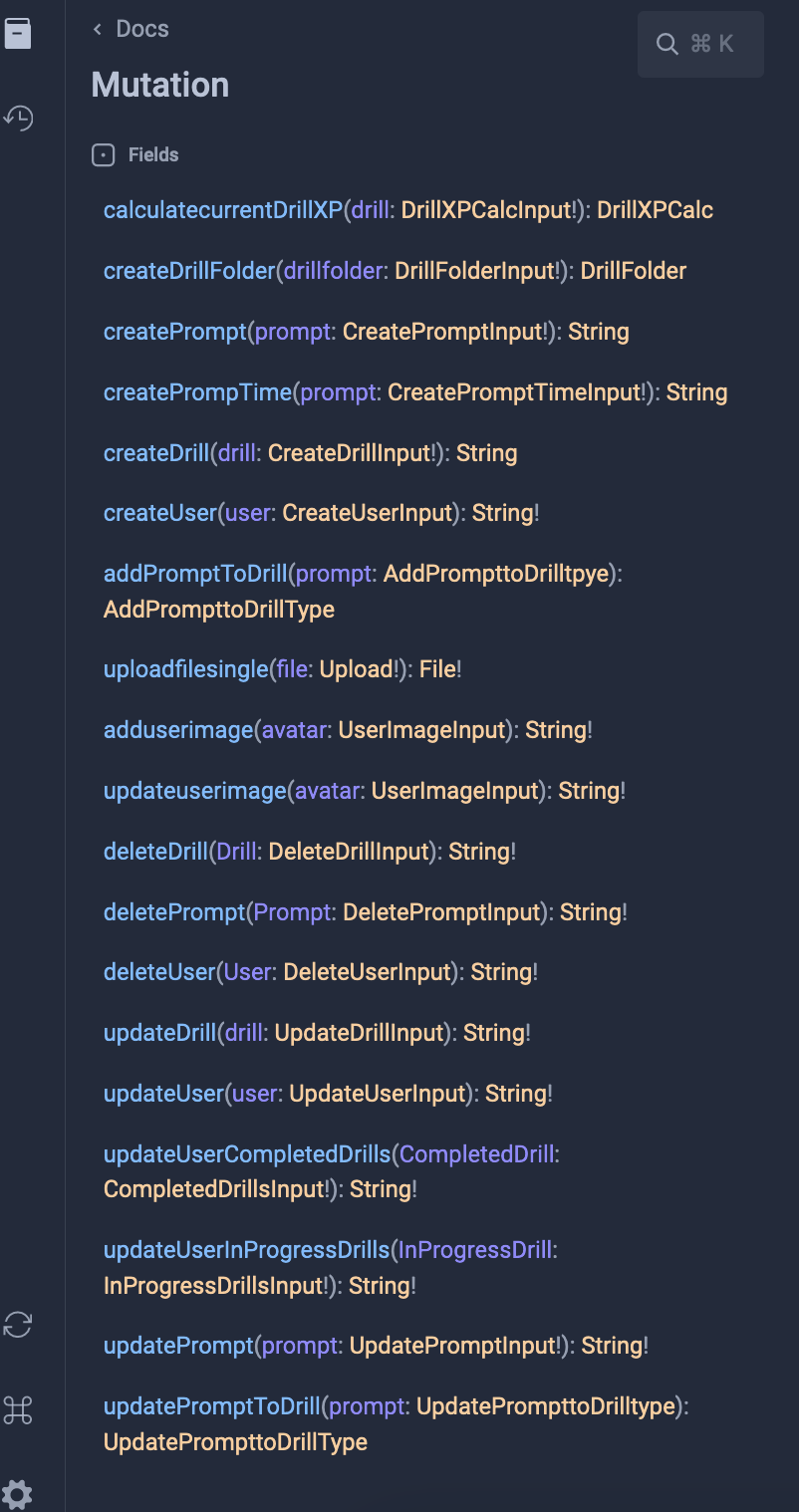

So we’ve covered the backend’s primary programming language and some of the characteristics we found useful when using it. However, there is another aspect to our backend that bears review. I’m referring to GraphQL, which is the API query language and associated framework that we used alongside Go for the backend. GraphQL exists in the same space as the technologies behind RESTful APIs and GRPC (they all have very varied pros and cons, but generally are the options that developers decide between when building API based backends). Some of the features of GraphQL that we took into consideration when choosing it as part of our stack include its strongly typed schema based requests and its efficient data retrieval, which allow it to simplify the backend in scenarios that typically require multiple endpoints in a REST based design, This also allows it to retrieve data without creating any over or under fetching issues. An important aspect of GraphQL is the queries and mutations. In GraphQL, any type of request that reads data (aka a GET in the RESTful world) is a query. On the other hand, any other type of request that alters data (in REST, these would be a DELETE, POST, or PUT call) is a mutation. With all that said, I know everything I’ve mentioned so far might seem a little abstract, so I think jumping straight into the examples is called for here.

Show me the Thing

Let me set some concrete context before going into some code examples. First, while GraphQL is the query language we used, the specific library that our backend is built with is the gqlgen library, which was built by the team over at 99designs (https://99designs.com/) for building GraphQL servers. This library has a ton of really great functionality, including the ability to work in the GraphQL playground to run your queries directly through a user-friendly interface, similar to Postman. This library also supports code generation, which takes care of a lot of the work around project scaffolding, GraphQL data types, etc. Now, for the part everyone has been waiting for, the actual code.

We’ll start with getting a project started using the gqlgen library. For a general non project specific introduction, you can follow along with their “Get Started Guide” found here, https://gqlgen.com/getting-started/. I’ll go ahead and share some of the initial steps from there to get us going and then we’ll see some content that is more unique to our particular use case and code base.

1. Assuming you’ve already created your project directory (mkdir yada yada) and find yourself within that directory, go ahead and initialize it as a go module, “go mod init github.com/[username]/projectdirectory”

2. After you’ve done that, add gqlgen as a tool dependency to that module (go get github.com/99designs/gqlgen) and run your go mod tidy command. At this point, if all has gone well, we can run the gqlgen command that will generate some of the project scaffolding for us. From within your project directory, run this command, “go run github.com/99designs/gqlgen init”

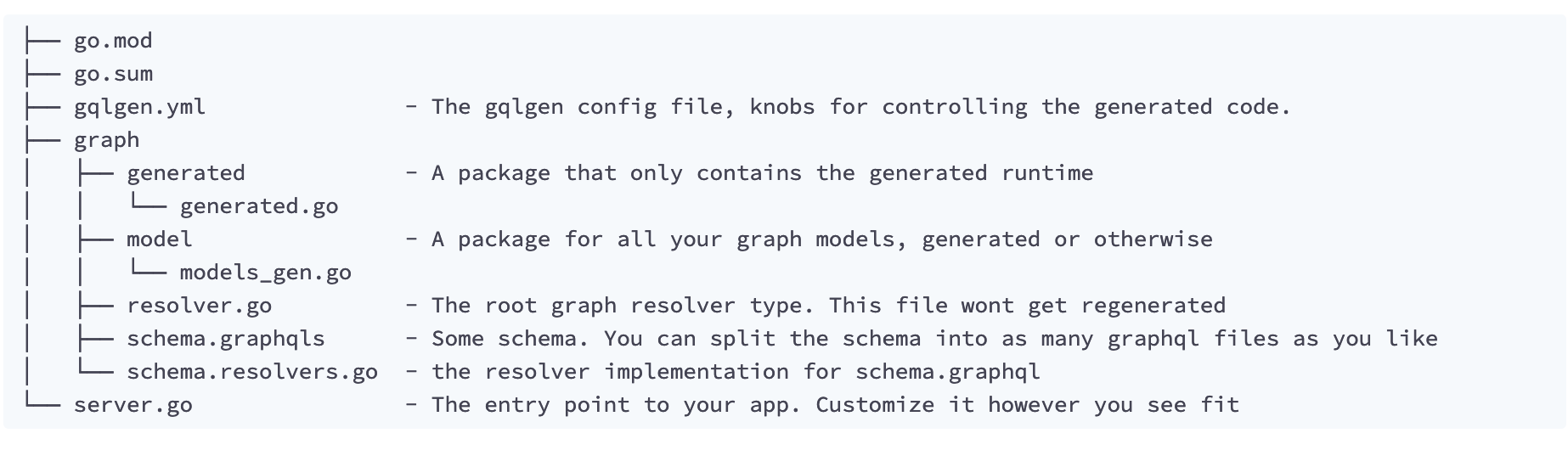

You will end up with a project directory with a structure like this:

3. After this code generation is done, you will find default schemas for your API in the schema.graphqls file. We edited those schemas to match our data models (you should do the same for your project), as shown below:

You’ll notice a lot of different things happening in this file. You can think of these different objects along these lines:

The Query and Mutation type definitions are how we tell GraphQL to generate each type of request, providing specifications on what inputs to expect and what outputs to expect and their respective types. As an example, our createPrompt mutation is expected to have an input of a CreatePromptInput object and a string output // response.

The input types are our specifications on what fields make up an input object. Going back to our example, the CreatePromptInput type is made up of these fields and their respective data types:

- PromptText: String!

- PromptName: String!

- CreatedBy: String!

- TimeLimit: Int!

- Base64: String!

- Status: Boolean

- ExperiencePoints: Int

- Difficulty: DifficultyEnum!

This type of paradigm is seen with Queries as well. In our Query type definitions, we see a get drill query that has an input of an object known as a DrillQuery and responds with an object known as Drill. According to their defintions, a DrillQuery is an input type with a single field, “DrillID” that is a ID data type, while the Drill output is an object defined with the following fields:

- DrillID: ID!

- PromptAmount: String!

- DrillName: String!

- CreatedBy: String!

- CreatedOn: String!

- PromptFolder: [PromptTime!]

- DrillDescription: String!

- Public: Boolean!

- ExperiencePoints: Int

You may notice something unique about one of the fields in this schema. The PromptFolder structure is an array of prompts, so in order to have our schema reflect that, we have to create a schema for an individual prompt (as seen in the schema file) and specify that it must be an array ( hence the brackets []).

These are merely selections of some examples from our project meant to show how GraphQL models data and allows us to edit schemas to match our objects and their data types (we ended up having a lot more data models in our schema but kept it limited to these for the sake of simplicity).

With the schemas designed, we can run the init command again from our earlier steps to update the generated files with our new schemas. After this command is run and our code files are generated, we can move to the graph/schema.resolvers.g file and implement the business logic that will interact with the schemas we have designed. This logic will be part of the empty extensions in the file, which just look like very sparse functions, something along these lines:

This function (or extension, whatever you prefer) at this point just panics and returns a message saying “not implemented”. Your particular project will have its own requriements regarding the business logic, but in our case, this function is meant to create a drill so it will need to receive the data from the request, connect to our Mongo database, and insert the drill. The logic to do that is:

Another example of an extension is our CreatePrompt logic. Originally, it looks much like the empty functions from before:

After we implement our business logic, it ends up looking more like this:

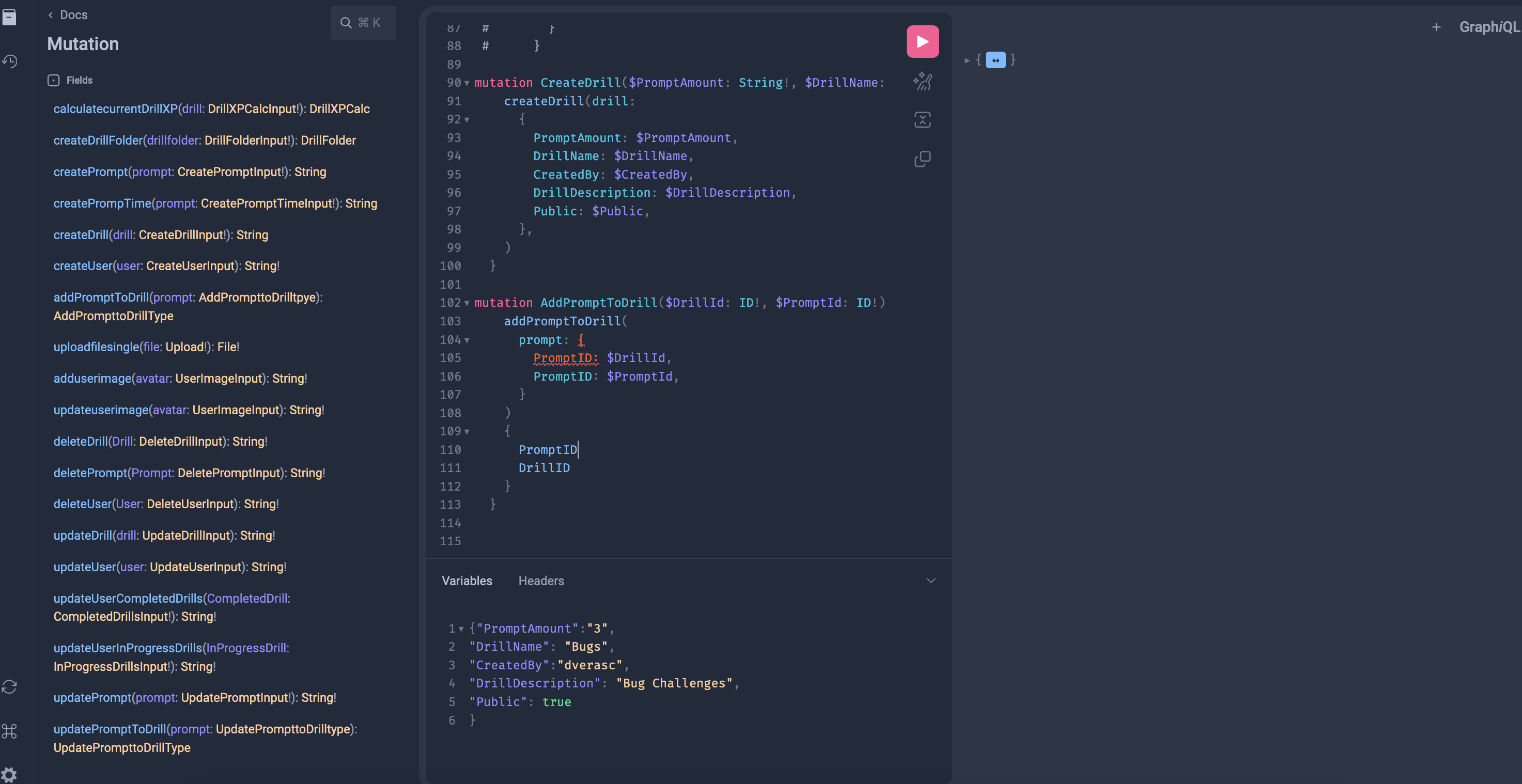

4. Okay, now that we showed off some of the actual logic, let’s assume you’ve completed all your extensions and are ready to test your APIs. To test your GraphQL API server, you should run the command “go run *.go” or “go run server.go”. The default server.go file that is generated by the gqlgen library should be ready to run locally without any changes required to the server code. Assuming this command runs wihtout any issues, you’ll be able to navigate to the address, “localhost:8080”, on your browser and start interacting with the GraphQL playground and your APIs. It’ll look something like this:

The playground has a couple really cool features that I’ll go over. First, it documents your schemas for you and has them available on the left hand side. This makes it very easy to reference when building your queries and mutation requests:

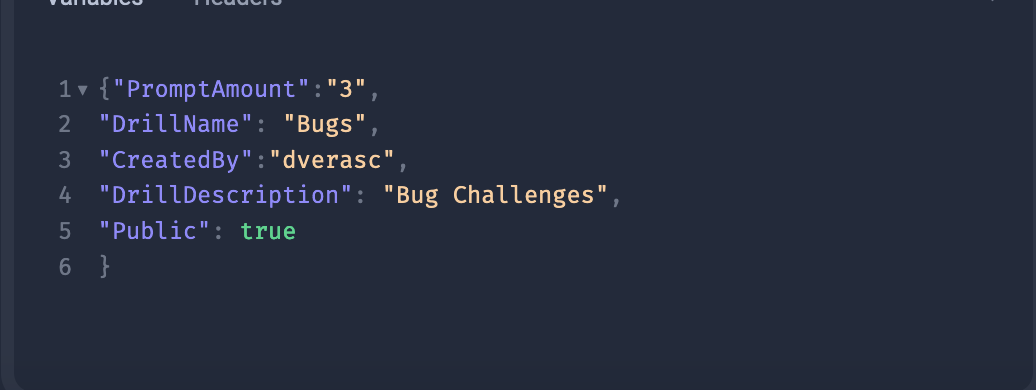

It also allows you to set data to variables instead of hardcoding it to the body of the request:

⌗

⌗

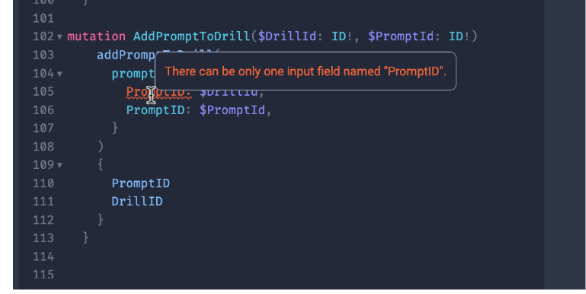

And it provides helpful feedback to help you write your queries and mutations properly:

In short, the playground is something like a combined IDE and API-tool (it’s basically Postman or Insomnia).

Bonus content: Okay so at this point you can see the high-level way our backend stack works. Using the gqlgen library, we can design our data schemas and generate the appropriate scaffolding that will then provide extensions that we use to implement the logic we’d like to see take place when a query or a mutation is called. This works pretty well out of the box, but if you’re interested in using this type of backend for something larger than just playing around with APIs, you’ll need to do some work on the auto-generated code to support certain functionality. As an example, in our use case, we needed the API server to support CORS (aka “Cross-origin resource sharing”), since our front end code would be calling the APIs depending on what front end elements the user interacted with. The generated server code doesn’t have CORS set up out of the box, so here is how we edited ours to support CORS:

Conclusion

If you’ve read along thus far, great job (I appreciate you putting up with my writing). This short primer is meant to provide a high level look at the DrawDrills backend stack and show some of the functionalities that we took advantage of. There is a lot more content and work that can be done with these technologies, especially when leveraging the gqlgen library. If there are questions or things we missed that you as a reader would like to us to elaborate on, please reach out to me or our team directly and I’d be happy to expand on it. Otherwise, if you’re interested in trying out DrawDrills, we are currently undergoing our beta roll out and accepting users here, drawdrills.org/register. Keep an eye out for updates as we finish our beta release and ramp up to our official product rollout!